Michael J Fox’s continuing role on “The Good Wife” and other programs has been a singular example of an actor willing to reveal a disabling illness, testifying to Fox’s professional commitment and his openness to disclosure.

Both things are praiseworthy, but the latter is remarkably rare in a media economy so predicated on bodily perfection and endless youth. Ben Brantley writes in a recent New York Times review of several theater groups that are doing similar work, however – as they foreground forms of disability and “difference” among actors that typically never get revealed or seen on stage or screen. As Brantley writes,

“Theatergoers generally expect actors to abide by certain longstanding conventions, and if actors fail to oblige, it usually isn’t intentional. We assume, for starters, that people portraying other people are going to speak so we don’t have to strain to understand them. Emotions, even mixed emotions, should be rendered with comparable accessibility and with a flow that passes for a smoother, larger version of the real thing.

“We should never, ever be aware of the gap between actors and their roles, a state that suggests that the performers are either miscast or inadequate, nor of the effort or strain that goes into creating the illusions of other lives. (Theater is not an athletic event.) And heaven forbid that any performer should directly or indirectly question our responses to a performance as it is occurring.

“Well, that’s the way it is on the mainstream stages of Broadway, anyway. But had you stepped into the well-packed margins occupied by more adventurous theater artists in New York in recent weeks, you would have heard the crashing, tearing sounds of every one of these rules being willfully shattered and shredded.

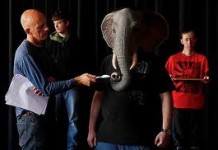

“Consider, for example, the close-attention-demanding ensemble that animated the Australian-born “Ganesh Versus the Third Reich,” in which most of the cast members had “intellectual disabilities.” Or the Israeli troupe of blind-and-deaf performers in “Not by Bread Alone.” Or the actors who chose to act badly in “Inflatable Frankenstein” and “Seagull (Thinking of you).” Or even the British chap who showed up — in a children’s theater production, no less — to confront young audience members about why they were laughing at his character, a tattered refugee from Shakespeare, in “I, Malvolio.”

Full story at: http://artsbeat.blogs.nytimes.com/2013/01/24/theater-talkback-defying-expectations-off-broadway/?ref=disabilities