The last few months have seen my campus scrambling to get back to in-person assessment and to reopen testing centers. Like many universities that quietly had deemphasized such exams during the COVID years, now at UC Irvine there is rising faculty demand to quickly change course. Many worry about the validity of take-home and online assessments, as campus officials search for rooms or even build new ones. Meanwhile, already stressed students feel increasingly desperate over high-stakes tests that can make or break academic success. While the crisis seems recent at UCI, what’s really happening predates the rise of generative AI and won’t be fixed with more exam rooms.

Much of higher education now sees online assessment as an arms race it can’t win, with over 150 institutions planning to end it this year. Earlier this month, the Law School Admission Council (LSAC) announced t it would return the LSAT to in-person testing by summer 2026, citing “security concerns,” “score inflation,” and “the misuse of technology to facilitate cheating.”[1] All Ivy League schools also are reverting to standardized tests for admissions after eliminating them during the last decade. Complicating matters further is the reality of cash-strapped schools facing infrastructure bottlenecks because they’ve repurposed or sold off testing centers.[2] Driving this frantic backtracking is the logical but incorrect belief that assessment is losing meaning at a time when ChatGPT can generate answers in a few seconds. Hence the current retreat to blue books, testing rooms, and internet-free conditions.

“Generative AI did not create assessment issues. It revealed them,” according to Emma Ransome of Birmingham City University.[3] Ransome explains that traditional measures like timed exams, standardized tasks, and recall-based tests historically have done poorly in evaluating skills universities claim to instill such as critical thinking, ethical judgement, and synthesizing ideas. Generative AI has made the disconnect between what is being measured and what is being taught even more apparent.

If a large language model can successfully complete a multiple choice pharmacology exam, or if an LLM can generate a decent survey essay about the causes of World War I, one shouldn’t be asking how to stop students from using it. Instead the issue should be what kind of knowledge those conventional measures assessed in the first place.

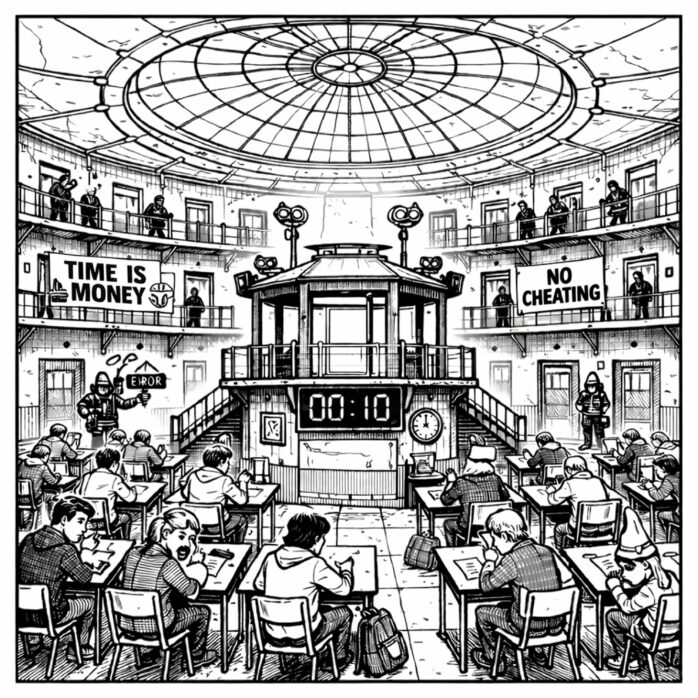

There are serious implications to the renewed testing craze. Racing to ramp up policing (i.e., developing stringent regulations, enhanced surveillance, proctoring technologies, and AI-detecting software) will add work for faculty and students with little learning increases. In many ways this climate reproduces, in digital form, the logic of Jeremy Bentham’s Panopticon, the eighteenth-century prison design in which inmates could be observed at any moment without knowing when they were actually being watched. The purpose of that design was not constant surveillance but the internalization of surveillance though self-policing. University exam systems increasingly operate on the same principle, replacing intellectual curiosity and autonomous learning with managed behavior under the threat of observation.[4] Add to that that AI-detecting software is notoriously untrustworthy, ethically suspect, and huge source of distrust and anxiety.[5]

When punitive policies dominate, student behavior shifts toward avoiding risk rather than engaging cognitively. Most ironically, universities may succeed in catching students who are using AI tools to support recall-based testing while failing to equip those same students for a professional environment in which generative AI is both omnipresent and irreversible.

How does the professional work environment use digital knowledge? To illustrate with an example that has remained with me, my personal physician consistently and openly consults a computer during consultations. The doctor references information in real time for drug interactions, dosage thresholds, and current diagnostic criteria. No apologies ever are made for this and I am reassured by the external verification. What my physician’s education has provided is not the minutiae of all of metrics and differentials, but the ability to evaluate symptoms, connect them to my history, develop effective reasons for decisions, and act on them effectively. The computer is more an extension of clinical inquiry than a replacement for clinical judgment. This is precisely what our students require, and it is precisely what high-stakes, closed book, proctored recall testing work against.

An alternative is emerging from recent educational research termed “Assessment as Learning,” which urges educators to rethink the purpose of testing entirely. Rather than treating exams as verification tools to confirm what students know under artificial conditions, Assessment as Learning views the test process itself as a site of cognitive activity, a location in which students make decisions, justify their reasoning, and demonstrate their comprehension in ways that cannot easily be outsourced to a tool.[6] This is not a softer or less stringent standard. It is a more difficult and a more educationally relevant one. In practical terms, this shift asks educators to design assessments around the knowledge application rather than factual recall. Assessments ask students to apply a theoretical framework to unfamiliar data, to analyze previously unseen cases, to solve open-ended problems, or to justify a stance in real-time questioning. Examples include oral defenses, iterative projects documenting processes used, portfolio assessments of development over time, and collaborative tasks that involve negotiating or dividing intellectual labor. While none of this is totally immune to AI cheating (nothing is anymore) the method calls for types of higher-order cognition that AI cannot replace, such as abilities to synthesize concepts across different contexts, render situated judgments, and take responsibility for a claim.

A growing body of research makes clear that the problems facing assessment today predate generative AI, although AI has certainly increased the urgency to address them.[7] Successful redesign strategies rely on how institutions define the purpose of testing, whether instruments are honest in their alignment of evaluation to learning objectives, and if institutions are willing to invest in the skilled work of assessment design. Ransome is correct that superficial substitution like swapping written essays for oral presentations without considering the underlying task will simply recreate the same problems in a different format.[8]

Across the broader academic landscape, the scramble to establish testing centers is understandable as a crisis management strategy. But adding more proctored rooms won’t close the gap between what assessments measure and what graduates will need to do. Adding more exam rooms won’t restore confidence in credentials if those credentials are only meant to verify that a student can regurgitate facts under surveillance. Beyond this, adding more proctored rooms will not address the fundamental question that AI has finally brought to the forefront: what is higher education for, and how do we know when it has succeeded? The assessment crisis is not a technological problem to be addressed through room scheduling and plagiarism detection. It’s a long overdue and urgently needed call to create something better.

[1] Law School Admission Council, “LSAC Announces Transition to In-Person LSAT Testing,” press release, February 2026.

[2] “How Standardized Testing Is Being Recalibrated,” Freedonia Group Report, January 2026; and reporting on high-stakes testing by WBUR/Associated Press, January 2026.

[3] Emma Ransome, “What Generative AI Reveals About Assessment Reform in Higher Education,” Birmingham City University, 2025.

[4] Jeremy Bentham, Panopticon; or The Inspection House (Dublin: T. Payne, 1791). The surveillance logic of the Panopticon was influentially theorized for modern institutions in Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Pantheon Books, 1977).

[5] Ibid.

[6] Ibid

[7] Australian Government Department of Education, Assessment Reform for the Age of Artificial Intelligence (Canberra: Australian Government, 2024). Referenced in Ransome, “What Generative AI Reveals.”

[8] “What Generative AI Reveals.”